It’s now been two weeks since we heard the news of the murdered hostages – six holy souls who were executed in cold blood after enduring eleven months of torture at the hands of their Islamist captors. The news hit everyone in Israel quite hard, and it cast a shadow over the normally hopeful first day of school. Since then quite a few more innocent Israelis have been murdered or killed, including a policeman whose own daughter was killed defending the Sderot police station on October 7th. Yet even as a society that has been completely bombarded with tragedy over the past year, the uniquely cruel nature of these deaths, compounded by newly released footage of the horrific conditions in which they are kept, has left many of us struggling to find the conceptual vocabulary to reflect on the events unfolding around us.

Since everyone in Israel is separated only a few short degrees, one name that particularly seared me on September 1st was of the hostage Almog Sarusi, a handsome 27 year old who was abducted from the Nova festival. Almog’s father Yigal owns an electrical shop in Ra’anana, around the corner from where I live. Almog was a charming, thoughtful, engineering student who loved nothing more than to explore Israel, play guitar, and spend quality time with his family and friends. He attended the music festival with his longtime girlfriend Shachar and stayed behind to help her when she was shot and severely wounded (she later died.) Since his abduction, his parents fought tirelessly on his behalf, exhausting every political and spiritual resource they could muster. The Sarusis don’t define themselves as “dati,” or religious. Yet Yigal nobly stood nearly every Friday on the corner outside his electrical shop requesting passers by say a tefilla or a bracha in the merit of his son Almog’s safe return. My friend Tamar accompanied him and provided home-baked cookies and boundless energy to find recruits on the sidewalk. Unlike some of the other hostages, there were no videos released of Almog during his captivity, and we didn’t know with any certainty the status of the young man for whom we prayed. My first thoughts when I heard the news on September 1st was that perhaps these prayers did keep Almog and the others alive for 11 grueling months. My subsequent thoughts, of course, threw me into a theological rut from which it was harder to emerge.

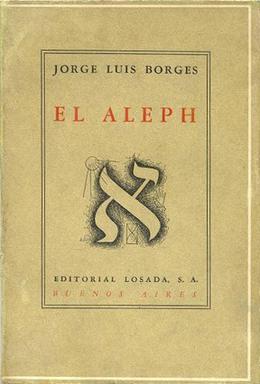

The 1943 short story “The Secret Miracle” by the Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges depicts a Jewish man named Jaromir Hladik, a moderately well-known author and playwright, who is earmarked for execution by the Nazis. Hladik is terrified by the prospect of death, but he is also terrified that he will not have the chance to finish his magnum opus, a verse drama called The Enemies. In the darkness of jail cell he prays to God ,“Thou who art the centuries and time itself,” to give him some extra time. And indeed, in a “secret miracle,” God gives him a year to complete his play in the privacy of his own mind: “the German bullet would kill him, at the determined hour, but in Hladik’s mind a year would pass between the order to fire and the discharge of the rifles.” The story raises interesting questions about whether there’s such a thing as a perfect work of art, even if it is entirely disconnected from an audience or context. By extension, it also explores the meaning of consciousness, and celebrates the value of life, of perception, and of artistic creativity for its own sake. These lofty concepts contrast with the Nazis for whom all of this could be snuffed out for the most shallow of reasons. At the end of the story, Hladik is murdered like countless other Holocaust victims. In an act of magical realism, he experiences a secret miracle that allows him to observe, feel, and create, albeit unbeknownst to anyone else, for a precious additional year’s time.

The six recently murdered hostages survived nearly a year under the most horrific conditions and are now dead. Recalling the “secret miracle” of the Borges story, what did those 11 months mean for Almog, Hersh, Eden, Ori, Alex and Carmel? What kind of torture did they endure? Amidst their suffering, what sort of sanctuary did they find, in their thoughts, in their environment, and with each other? What gave them strength, and what sort of discoveries did they make, about themselves and each other, about life, and about God?

Almog’s family sat shiva in a park next to pastoral green walking paths in Ra’anana. Many people from all walks of life came to pay their respects. We sat for a bit with Almog’s father Yigal, who spoke with remarkable composure, deftly balancing sensitivity to the various parties in front of him: two bashful seminary-age girls, another pair of women with tall head coverings who had driven in from the Shomron, and Noam Tibon, the retired army general turned October 7th hero who is firmly on the left politically. Yigal spoke about Almog’s love for the land of Israel, his sensitivity for others, how his army friends call him “Abba,” because he was the sort to always take care of those around him. He also spoke about the complexities of his own efforts to free his son. He did not believe in a hostage deal “at any cost,” but he believed that in the absence of complete victory over Hamas then the hostages had to be prioritized. His comments kept drifting to the 6 martyrs, the 6 “kedoshim” he called them. He said that Almog loved to have deep conversations, and he imagined what sorts of things they spoke about together. In his better moments, he thought of Carmel Gat doing yoga exercises with them, of how they must have given each other strength and solace until the end.

He also spoke about how even in this most devastating of circumstances, “miracles” had occurred. It’s a miracle his family could bury Almog with his body intact. That only several short days after he was killed they could stand at his gravesite and give him a proper funeral that paid tribute to his many wonderful qualities. And maybe other miracles too, he wondered aloud. I thought of his weekly efforts to canvas for tefillot near his shop on Ostrovsky Street.

It’s hard to say what constitutes a miracle and what is precisely the opposite. Even in the Borges story, one can dwell on the “miracle” experienced by the protagonist, or the pure and unadulterated evil that led to his predicament in the first place and ultimately his murder. I have heard so many wonderful October 7 miracle stories and it is hard not to be moved by them. But then there are the “non-miracles,” the Nova escapee who survived hours in the woods only to be killed by a fresh wave of terrorists, the hostages who were killed just hours before their rescuers arrived. In these circumstances we are left looking for more modest sources of consolation. Maybe this is the meaning of a “secret miracle,” not only a miracle that happens in secret, but a miracle that we manage to see or experience even when everything else seems to have gone wrong. Moments of strength, courage and love in a dark and claustrophobic tunnel. Even the sheer miracle or life itself, sustained for so long in an environment so hostile to it. Or the miracle of the resilience of the Jewish people. A father in immeasurable pain who raises his eyes to God and also to others, managing to transcend an impossible circumstance with an expansiveness of spirit that itself is also a kind of a miracle.