“My teacher used to say that we must learn to stay with a difficult question for forty years. Not to let up, and not to despair. Then there is a chance that we will reach the truth.”

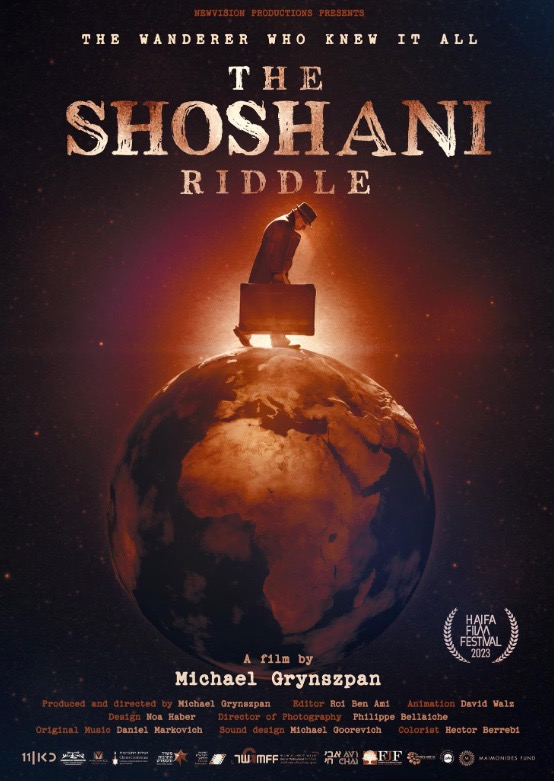

Amid the chaos and trauma of October 7, 2023, one of the innumerable cultural events deferred was the release of a unique documentary about the elusive Monsieur Shoshani. Shoshani’s mysterious persona, brilliance, and iconoclastic disposition have been the stuff of legend since he emerged from Europe after the Holocaust (he is depicted on the movie poster as a hunched-over figure carrying a suitcase). Shoshani was purportedly a master of Jewish tradition, Western philosophy, mathematics, science, and as many as thirty languages. He taught Torah everywhere he went—France, Morocco, Israel, and Uruguay—though what, exactly, he taught and where he came from remain a mystery. His students ranged from scholars and physicists to farmers and Holocaust orphans.

After he met Shoshani, the great French Jewish philosopher Emmanuel Levinas famously said, “I cannot tell what he knows; all I can say is that all that I know, he knows.” His gravestone in Montevideo, Uruguay, reportedly paid for by Elie Wiesel, reads, “His birth and life were sealed in a riddle.”

Although Shoshani’s life remains shrouded in mystery, the curtain seems to be drawing back, at least a bit.In 2021, the National Library of Israel announced Shoshani, whom Levinas once called “the Oral Torah in his entirety,” had left dozens of notebooks behind. Some of these cryptic notes…had been preserved in a secretive trust by four of his students since 1969. Another trove was donated to the National Library by Professor Shalom Rosenberg, an Argentinian-born scholar of Jewish thought at Hebrew University who became close with Shoshani toward the end of his life. For the last fifteen years, French Israeli director Michael Grynszpan has toiled and puzzled over the notebooks and the life of their author. His result is The Shoshani Riddle, which chronicles Grynszpan’s hunt for Shoshani and his attempts to piece together the master’s life story.

For the full review of this wonderful film, please the new Winter issue of Jewish Review of Books.