In Chaim Potok’s classic novel My Name Is Asher Lev, a young Chasidic boy tries to integrate his religious faith with his prodigious artistic talent. In school he scribbles on the margins of his sacred books. On weekends he takes clandestine trips to view Renaissance art at the Brooklyn Museum. Throughout the novel he grapples with the question: Is art something that brings us closer to G-d and to the Jewish people, or does it operate on another plane entirely?

Asher Lev is a member of the Ladover sect, a thinly disguised stand-in for Chabad-Lubavitch, and the beloved Ladover Rebbe gently explains that it makes no difference whether a man is a shoemaker or a lawyer or a painter; rather, “a life is measured by how it is lived for the sake of Heaven.” Yet, despite the Rebbe’s encouragement, ultimately Potok’s book insists that the chasm between the life of a Chasid and that of an artist is impossible to fully bridge.

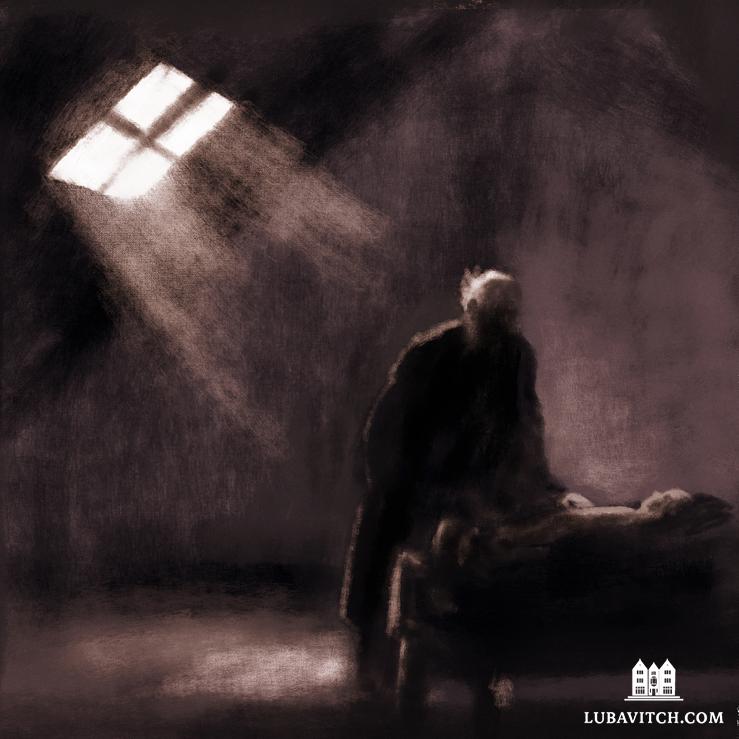

The role of visual art in the religious Jewish worldview has always been somewhat tenuous. This may be rooted in the Torah itself: the second of the Ten Commandments prohibits the creation of graven images and the “likeness of any thing that is in the heavens above, that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth.” But it may also be an accidental byproduct of history: the destruction of the Holy Temple in Jerusalem in all its aesthetic glory, the exclusion of Jews from artistic guilds, and the overwhelming dominance of Christian iconography in the history of Western art. While Jewish decorative arts abound—micrography, illuminated manuscripts, silver Judaica items—Jewish representation in the fine arts, at least prior to the modern era, is decidedly less pronounced. And while Jewish individuals have achieved prominence as modern artists, they tend toward secularism and individualism in both worldview and artistic language. We have yet to see a uniquely Jewish artistic idiom arise—that is, a path forward for an artist who wishes to tie him- or herself to a Jewish tradition in visual art.

To read the full article please see the gorgeous art-themed Fall/Winter Issue of Lubavitch International Magazine.