Last week when President Trump announced his intention to clean out and rebuild the Gaza Strip, I don’t think I was alone in feeling something I had not felt in a long time. It was not the elation of giving it to ones enemies, or the smug satisfaction of political validation. It was a rather fragile feeling, somewhat tentative, one might even say naive. Throughout the war we have experienced crushing blows but also astounding, miraculous, successes. Yet in these victories there is often a cyclical dynamic: we conquer territory only to withdraw weeks later, we kill terrorists only for their ranks to be replenished by a seemingly infinite supply of hateful young jihadists. Even our genuine exhilaration at the return of a few of our hostages is marred by our fear of what’s to come from from the murderous and unrepentant terrorists who are being released in turn. As always, we trust in God and our military and wish for the best, but common sense tells us that, in good measure, the problems we face today aren’t going anyway time soon.

For real hope to blossom, we need to understand that change is on the horizon. Trump’s proposal, whether or not its likely to materialize, offers a rare vision that could potentially break the cycle in which we find ourselves. I was therefore surprised to notice a few American Rabbis and “Jewish professionals” pontificating on the matter with critical accusations of ethnic cleansing and the like. On second thought I suppose it’s not that surprising. Only someone who is not particularly starved for hope could look such a gift horse in the mouth. If Trump’s Gaza proposal leaves you ethically outraged, or even indifferent, this simply demonstrates your own removal from the pit of despair in which Israelis find ourselves since October 7th. In the days following his announcement, I have not spoken to any Israeli, on the right or the left, who does not feel just a little bit hopeful, or at least tickled, that a world leader finally has the courage to propose a way out of our current morass.

I don’t know if it is providence or simply an all-knowing algorithm, but last week a new song popped into my Spotify playlist called “Ribbon of Hope,” “Chut shel Tikvah,” written by the popular Israeli singer-songwriter Aaron Razel and his wife Efrat. The song was actually composed about a year ago, around the time of the first hostage release, when Razel and his wife were enjoying a beautiful day together on the Tel Aviv boardwalk. I understand those kinds of days as I’ve experienced many of them myself since October 7th. A lovely day when you have the chance to appreciate the beauty and wonder of daily life in Israel, with the sickening knowledge that all around us families are grieving, soldiers are fighting for their lives (and ours) on the battlefield and that dozens of our brethren are wasting away in the depths of Hamas torture dens. Yet this day was different, as Razel sings, there was a sense that something monumental is about to change.

Soon the gates will open

and soon

the sun will rise again

the wild flowers will fill the fields

with colors anew

until they do

we won’t forget the pain.

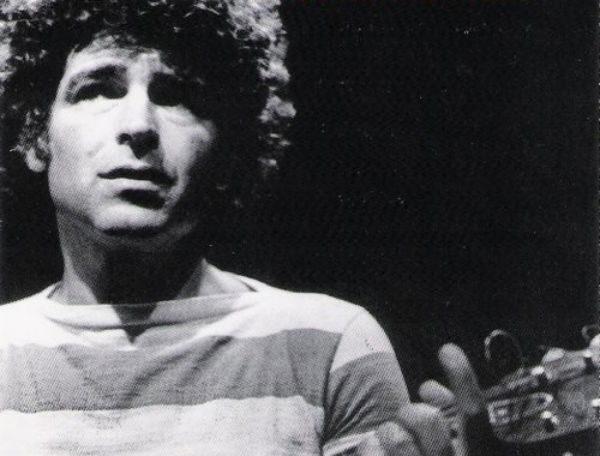

The song has a kind of 1960s, folksy feel, amplified by harmonica interludes by the famous Israeli musician Ehud Banai. Although it owes a debt to peace anthems from the past, there’s a difference here, a respect for the necessity of war and also, I think, a kind of underlying ambiguity that is not necessarily apparent on first listen.

Above in the skies

are the voices of war

while in our hearts

we long for comfort

And I, like a captured child

tie to my window

a ribbon of hope

Two allusions here may be familiar to listeners. One is the “ribbon of hope,” which likely references the Book of Joshua’s story of the harlot Rachav, who saves the Israelite spies in Jericho and hangs a red string from her window. Interestingly, in Joshua the Hebrew word tikvah means cord – but hints at the hope that Rachav and her family can ultimately be saved from the wicked society on whose edge they dwell. The ribbon in the song also is reminiscent of the yellow ribbon that has morphed into the ubiquitous symbol of the Israeli hostages imprisoned by Hamas.

The phrase “captured child,” is a translation of “tinok shenishba,” a Rabbinic term that refers to a Jew who was kidnapped by gentiles as a child and as a result cannot be Halakhically held responsible for his lack of Jewish observance. It could be that the Razels chose “tinok shenishba,” just for its associations with innocence and captivity, though I wonder if something else is being suggested here. The term “captured child” is used in Rabbinic literature in reference to sin, it allows us to relieve responsibility from adults who simply don’t know better.

Perhaps some of the implication here is that a certain kind of hope is indeed naive, and perhaps even wrong. We hope and pray for the safe release of our hostages, even if we know that under the current parameters it comes at a cost that is unforgivable. We dream of an end to the war, even if we know that ending it prematurely means passing on the baton to the next generation, that is to our own children and grandchildren. Yellow ribbons have become mixed symbols in our divisive national context. We all long for the return of our hostages alive and in good health. But the cars that sport yellow ribbons often have washed out anti-Bibi bumper stickers as well. Hostage Square is just around the corner from Kaplan Street, and despite many many fine efforts to steer things differently, the Hostages and Missing Families Forum is hopelessly politicized and pointed often in the precise direction of its potential allies.

Finding shared sources of hope and consolation in this environment can be challenging. Which perhaps is why the Razels chose to newly rededicate the song to Agam Berger, a 19 year old observation soldier and gifted violinist who was released in a recent prisoner exchange. Reports about Agam have captivated the Israeli public since they filtered out after the first hostage deal, how she refused to eat unkosher meat or clean or cook for her captors on Shabbat, how she lovingly braided the hair of female hostages before they were released, even though she was forced to remain. Her first message to the world upon her release (in exchange for 50 craven terrorists) was “I chose the path of faith and in the path of faith I returned.”

Amidst all the protests, uproar at the Knesset, burning trashcans on the Ayalon, we are presented with the image of one brave young woman clinging to her faith, using it to hold up herself and others, and in doing so uplifting her nation as well. This also is a version of hope because it presents us with another path. If the hostage crisis has been used as yet another wedge to pointlessly drive us apart, perhaps the purity and heroism of these individuals can also help us find a way to move forward together.

The new addition of the song includes an added stanza that honors Agam. The line “who is this coming up from the desert” is a quote from the Song of Songs, and can just as easily be applied to the Jewish people leaving their Egyptian captivity. In the song it also refers to Agam:

And I ask

who is she

who is she

who rises up out of the desert

And I hear

I am she

I am she

clear as a lake (agam) of rivers.

Both Agam the person and also the sparkling water imagery with which she is associated, adds the presence of something refreshing and new. A new shot at national unity, at spiritual consciousness, and for her and her family, a new chance at life – it is not a coincidence that the Hebrew words mikvah and tikvah are related. And now, “on the horizon/ are days of hope/the waves whisper their faith.”

Personally I don’t know anything about what the coming years, months, or even days will bring. None of us do. But we can be grateful for the mere chance to be a teeny bit closer to breaking away from a rotten paradigm that has brought so much bloodshed and destruction – toward something new, “rising up from the desert.” Maybe things won’t exactly pan out in the way that the American president, and all of us, dream (there may also be some differences there). As for me, I’m still going to cling to ribbons of hope.