In the early hours of June 13 my family and I, like all Israelis, were awakened by the shrill sound of a phone alert. Israel had preemptively attacked Iran’s nuclear facilities. Momentous news, but I promptly put my pillow over my head and went back to sleep. Only when we woke up again later that morning did we realize that something historic had occurred. We also understood that a challenging period lay ahead.

We had only recently moved into a new home and, despite Houthis sporadically firing missiles in our direction, we had grown lax about running to our safe room, what Israelis call a mamad. Ours was filled with dust and leftover construction material. But on the day of the phone alerts—once we’d grasped the gravity of what was happening—we got to work. We spread a plastic mat over the floor, brought in a spare mattress, and set up a pack-and-play crib. The missile fire from Iran began in earnest that evening.

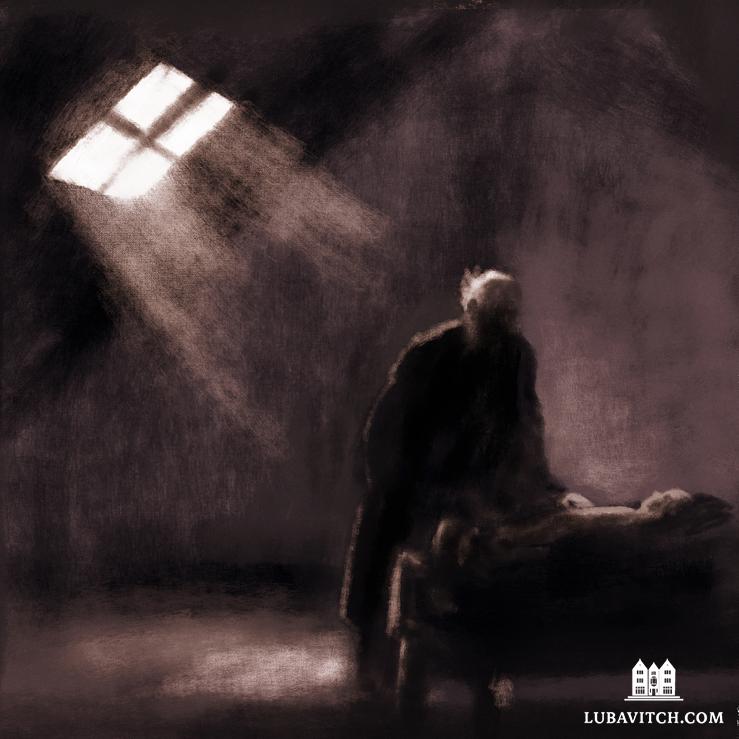

As the days wore on, we adjusted to the confines of this small space where emotions vacillated between fear, comfort from the presence of those we loved, and occasional irritation by those very same people. One mattress turned into four—each of our seven children laid claim to their own little spot. The more time we spent in our safe room, sometimes joined by friends or near strangers who needed a place to shelter, the more we acclimated ourselves to its deprivations and, occasionally, to its surreal benefits. Sociologists talk about the “third place,” which is an additional living space beyond home or work, like a synagogue, for example. These places expose us to people, ideas, and experiences beyond our immediate family and daily routines. During Israel’s twelve-day war with Iran our safe rooms also became a third place, introducing a new mentality and way of being that removed us from our day-to-day lives.

Read the full article, just recently posted online, from the Fall issue of Lubavitch International Magazine.