The Bible Lands Museum in Jerusalem is known for its collection of Near Eastern antiquities from the Biblical period. Yet amidst its galleries stands a startling cultural artifact of far more recent origin.

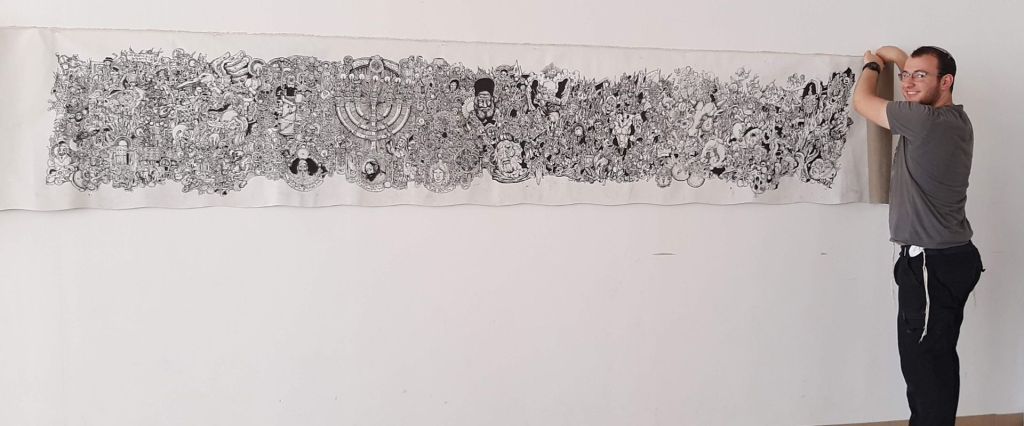

Kuma—meaning “Rise”—is a nearly ten-foot-long scroll depicting a dense, vivid, intellectually rich, and aesthetically stunning account of Jewish history. Its full title, “Kuma, Mei Afatzim ve-Kankantum,” refers to the materials used to prepare ink for Torah scrolls and other sacred texts. Evoking an unfurled Torah scroll, Kuma is the high-school senior project of a brilliant young yeshiva student, artist and poet named Eitan Rosenzweig הי”ד. Staff Sgt. Rosenzweig, an Alon Shvut native and student in the Yerucham Yeshivat Hesder, served in the Givati brigade and was killed in Gaza in November 2023, at the age of 21.

Kuma weaves together Jungian theories of the unconscious, the mythologist Joseph Campbell’s concept of the heroic journey, and imagery drawn from Western art and Jewish history—some of which appear elsewhere in the Bible Lands Museum. Kuma also incorporates literary allusions to the Bible, Talmud, modern Hebrew literature, Eastern and Western general philosophy, and more. It is a work of art that one must study rather than merely observe.

The full essay can be read at Tradition Online.