Since March of this year, the Met Breuer, a new annex of the Metropolitan Museum, has hosted a remarkable exhibit called “Unfinished.” The works of art exhibited consist primarily of unfinished work from the Met’s permanent collection, including paintings by Rembrandt, Titian, Van Gogh, Klimt and many other noteworthy artists. Some of the works included were abruptly abandoned by their creators for various external reasons such as death, illness, or a more lucrative commission elsewhere. They feature unpainted spots of canvas, rough blurry lines or pencil sketches that are still visible. These pieces are striking in how they display the creative process of the artist at work – many display a startling unintended beauty in their incomplete form. Other paintings displayed, particularly the more modern works, were intentionally created with an unfinished or provisional quality, similar to a piece of jazz music.

Many of the pieces in the exhibit don’t fit neatly in either category however – they were neither accidentally abandoned nor purposefully designed to feel incomplete. These are works that an artist stops painting because he or she decides that it captures something essential in an unfinished state that would be lost once completed. Often these paintings were not made at the behest of wealthy patrons, or for the purpose of commercial gain, but rather remained in the artist’s personal collection. See John Singer Sargent’s outdoor scene of his sister and her friend for example, or Rembrandt’s intimate portrait of his housekeeper turned life partner Hendrickje Stoffels.

At their best, all three types of paintings challenge the notion that a “perfect” piece of art is always the most effective one. The unpainted spaces and rough backgrounds of these pieces give them a raw or urgent quality. There is a dynamism to them that would be lost in a more refined, yet calcified, final product.

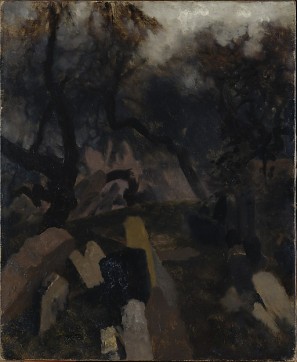

One memorable piece in the exhibit is a painting by the 19th century German artist Adolph Menzel entitled “The Jewish Cemetery in Prague.”According to the artistic standards of the mid-nineteenth century, this piece’s rough composition renders it technically “unfinished.” Yet the loose and fluid representations of the tombstones in the cemetery give them an air of impermanence that a more fully realized composition would lack. In reflecting the angles and colors of the trees above it, the Jewish cemetery feels less like a place of finality and more like one in harmony with the nature that surrounds it. By leaving this particular painting unfinished, the artist may be making a deeper statement about the nature of mortality itself, or perhaps the way in which society normally entombs the dead. That is, the unfinished nature of this painting of a cemetery implies that it affirms life rather than enshrines death.

Zecher L’Churban

An echo of the “unfinished” aesthetic may be identified in the Jewish practices surrounding mourning. Upon hearing of a loss, a Jewish mourner traditionally rips his or her garment, and Jewish tradition is replete with rituals that reminds us of the incomplete nature of our happiness in the wake of the destruction of the Holy Temple in Jerusalem, which occurred in 70 AD. For example, if a Jewish family builds a new home, they are required to leave a visible patch of it unplastered – in a sense the home remains unfinished as a reminder that God’s “home” has yet to be re-built. Reflecting upon a patch of unpainted canvas in the otherwise complete “Street in Auvers-sur-Oise” by Vincent Van Gogh at the Met Breuer, I was reminded of this uniquely Jewish practice, known as a “zecher l’churban” (a reminder of the destruction) .

There are a variety of customs that are associated with zecher l’churban, some of them more widely observed than others. For example, a glass is shattered under a Jewish wedding canopy, women are instructed not to wear all of their fine jewelry at any one time, and in some circles even listening to music is curtailed. The pervasiveness of these customs does not reflect a sense of nihilism or a cult of mourning. Rather, the sages say that “whoever mourns over Jerusalem will merit to see in it’s joy” (Bava Batra 60b). Counter-intuitively, reminding ourselves of our incompleteness specifically points to the promise of an eventual restoration.

The “Unfinished” Aesthetic of Eve Grubin

This attitudes toward incompleteness, which informs the halakhot (laws and customs) of zecher l’churban, is brought to the fore by the contemporary religious Jewish poet Eve Grubin. American by birth, she currently lives in England and recently published a new chapbook of poems entitled The House of Our First Loving. Grubin is unusual among contemporary poets, even contemporary Jewish poets, in that her poems engage with religious tradition in a serious and highly erudite fashion. She draws on Biblical, Talmudic and Jewish liturgical sources with the same fluency that she channels poets like Emily Dickinson and Elizabeth Bishop. Like her first book of poems, Morning Prayer, the poems in her new pamphlet draw on a variety of Jewish themes. Throughout both collections, Grubin’s work strongly reflects the sensibility that animates the “Unfinished” exhibit at the Met Breuer and the zecher l’churban rituals as well.

For many, religion represents a worldview focused on a unified world brought into being by, and under the providence of, a unitary Divine being. However, Grubin’s understanding of Judaism is one in which concepts like broken shards and blank spaces are central. In the poem “The Great Oven Debate,” Grubin reframes the classic Talmudic argument “Tanur shel Achnai” (the oven of Achnai”), which is most famous for the statement of “lo bashamayim hi” (“[the Torah] is not in heaven”). The poem dwells less on this broad theological-philosophical statement and more on the shattered pieces of the oven itself. The speaker asks “Is the oven a whole vessel?/Or broken shards?” Her answer:

“Satiate me with our combined truths.

Let the clay coils be broken

And whole.”

As a writer, Grubin is also interested in modesty, both as a poetic style and an object of theological inquiry. In her first book of poetry, she explores the ways in which reticence, or the act of withholding gratification or fulfillment, translates into greater longing and desire. As she writes in the title poem of Morning Prayer:

“It’s not faith, it’s faltering.

Less happiness than the laws.

It’s not survival.

It’s the battle, desire and modesty, the name. Near.

Not near; awe.”

Here we see that for Grubin, longing is in some way the essence of Judaism and is equally, if not more central than the fulfillment of that longing.

Grubin’s nod to this dimension of Judaism in her poetry is even more compelling when one considers it in the context of other religions. In the magnificent poem “Jerusalem,” she contrasts a Christological post-redemption religious vision with the earth-bound legality of the Rabbis. The notion that the redemption of our world is yet to come, and depends on our actions, is foundational to Judaism. As Grubin writes:

“Keep me close to the flaw,

to the cracked soil. Don’t let me

fly up again; keep me living

Inside the laws, and the lightning, planted

and learning, leaning

into this difficult field.”

Just as a viewer might be drawn to the unfinished patches of canvas at the Met Breuer exhibit, Grubin sees a spiritual opportunity in the “cracked soil” of our world. Flaws and incompleteness are what keep the speaker tethered to the earth and to her faith.

“Unfinished”: A Poem

In a new poem entitled “Unfinished,” Grubin specifically connects this sensibility to the notion of zecher l’churban in particular. In this poem, the speaker suggests that incompleteness, while frustrating at times, may be a tie that binds a husband and wife to one another, and moreover may stimulate a longing for a greater religious redemption. “Who needs finality,” asks Grubin, “when unfinishing creates a longing for what has not yet happened?” While our incompleteness in an exilic, post-Churban world is painful and discomfiting, appreciating that incompleteness is an intrinsic part of Judaism and of the Jewish religious personality.

Unfinished

My husband has trouble finishing things.

When he washes the dishes

he leaves at least one pot in the sink and a few pieces of silverware.

He says that my writing about this

may constitute lashon hara, speaking negatively about others.

‘Not finishing things is zecher l’churban,’ he adds,

a way of remembering the destruction of the Temple

which stood in Jerusalem nearly two-thousand years ago.

Now he’s in the other room making the bed, which will look lovely

except for a few untucked corners, a pillow askew,

strange for a man who is slightly OCD, who can’t bear

a slanted piece of paper on my desk.

Yesterday, he almost

finished his article on Ælfric’s use of Latin in Old English prose,

and he began one of the tasks on his list of things to do.

Who needs finality when unfinishing creates a longing

for what has not yet happened?

Eve Grubin, “Unfinished,” from The House of Our First Loving. Copyright @2016 by Eve Grubin. Reprinted with the permission of the author.

The theme of the “incomplete” is in my view both very human and very Jewish. If throughout each of our lives, we are constantly “becoming,” something that goes beyond the Heracleitian idea of mere incessant change, then were we to freeze frame the progession in which we take part at any particular point, we should be struck by our incompleteness and the need to forge on to attain a greater wholeness or Shleimut. Zeicher LeChurban acknowledges a certain backsliding in terms of overall Jewish history; but that stands apart from each individual striving to achieve his/her own sense of Shleimut over the course of the years that one has been allotted . The Talmudic passage that speaks to this idea most succinctly in my mind appears at the end of Tractate Berachot, 64a:

“R. Abin the Levite also said: When a man takes leave of his fellow, he should not say to him, ‘Go in peace’. but ‘Go to peace’. For Moses, to whom Jethro said, ‘Go to peace,’ went up and prospered, whereas Absalom to whom David said, ‘Go in peace,’ went away and was hung.

R. Abin the Levite also said: One who takes leave of the dead should not say to him ‘Go to peace’, but ‘Go in peace’, as it says, ‘But thou shalt go to thy fathers in peace.'”

Yaakov Bieler

LikeLiked by 1 person

Beautiful! Thanks for these thoughts. I am also struck by that passage at the end of Brachot, there is a way in which not being in process/unfinished signifies death. I saw this in the Jewish Cemetery painting as well.

LikeLike

The counterintuitive idea underlying the “unfinished concept” is also reflected in the following:

Berachot 18a-b

(R. Chiya said:) … (Kohelet 9:5) “For the living know that they shall die:”– these are the righteous who in their death are called living… “…But the dead know nothing”:–These are the wicked who in their lifetime are called dead…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Also, really interesting!

LikeLike

Sarah I’m delighted to discover your blog. This was a beautiful post that masterfully drew connections between contemporary poetry, classical art, and traditional Jewish sources in order to highlight that everything is the creation of Hashem Echad.

Thanks for sharing these ideas.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Dalia! So excited that you’re reading 🙂

LikeLike

Pingback: Literary Voice as an Expression of Theology: The Examples of Deuteronomy and Lamentations – The Book of Books

Pingback: Frissons of Geulah – The Book of Books