Amid the later books of the Bible’s prophecies of destruction and accounts of divine retribution, the book of Ruth stands out. The midrash in Ruth Rabbah (2:14) states: “This megillah has no laws of purity or impurity, no transgressions and no mitzvot. So why was it written? It is just to teach how much reward comes to those who act with loving-kindness (chesed).”

In the context of the Bible, Ruth is unusually sweet. Sin, if present at all, remains in the background. Its characters must choose between the merely permissible and the exceptionally virtuous.

Orpah is not wrong to return to Moab, though Ruth is a heroine because of the unnecessary sacrifices she makes due to her loyalty to Naomi. The unnamed relative or “redeemer” who waives his technical obligation to Ruth is not held liable, but kinsman Boaz is valorized because he goes above and beyond his formal obligations. Brothers Machlon and Chilyon (trans. “Sickness” and “Wasting”) who, by virtue of their names alone are perhaps the least positive characters in the book, are not explicitly censored for any of their actions (see Rabbi Hayyim Angel’s recent article on this subject). Their deaths are terribly unfortunate, in the way that any premature death is, but they do not ultimately shroud the narrative in darkness or make it a tragedy. At the end of the book, due to the acts of kindness displayed by various characters within, sweetness and “chesed” prevail.

Ruth as a Tragicomedy or Romance

In Aristotelian terminology, the book of Ruth falls into the category of “comedy” rather than “tragedy.” For Aristotle, a play could only facilitate true catharsis if it was a tragedy, and tragedy is therefore widely considered the greatest of all genres. Yet, for many playwrights, this hierarchy is not a given. In a certain sense, the comedic vision actually most resembles the world in which we live. As a literary genre, a comedy isn’t a work that is necessarily filled with jokes or slapstick humor. Rather, the comic vision is one in which, despite bad luck or human folly, it is possible for things to turn out well.

Shakespeare is famous for tinkering with the categories of tragedy and comedy in many of his plays. Even a classic tragedy like Romeo and Juliet begins with signifiers that it will be a comedy. (The 1998 film “Shakespeare in Love” purported to explain why this would-be comedy eventually morphed into a tragedy.) Conversely, nearly every Shakespearean comedy contains dark or serious elements, including at the moment of conclusion when all is supposed to have been resolved. While Shakespeare achieved his greatest fame for his tragedies – Hamlet, King Lear and the like – the last plays that he wrote in his life, including The Winter’s Tale and The Tempest, were not tragedies at all. These plays are difficult to categorize – they are certainly not tragic because none of the important characters die at the end (or if they do, they are brought back to life). However, the term comedy seems too light a category to apply to them. Critics call these plays “tragicomedies” or “romances.” Although they reflect a vision of the world that is fundamentally comic in nature, this vision is no less serious and no less philosophically profound than a tragic one.

Intertextuality in the Book of Ruth

Perhaps the book of Ruth may be likened to some of these later Shakespearean dramas. Goodness prevails in the book, but not at the cost of totally effacing the tragic qualities that are present in both life and the Bible. This point can be demonstrated through a study of the book’s numerous intertextual Biblical allusions. Through these allusions we encounter an alternate universe in which human mistakes do potentially lead to tragic outcomes and acts of gratuitous kindness are few and far between.

For example, at the start of the book we learn that Ruth takes place “וַיְהִי, בִּימֵי שְׁפֹט הַשֹּׁפְטִים,” “in the days when the judges judged, “ a direct allusion to the book of Judges. Judges depicts one offensive or ugly event after another, with increasing intensity, until the book concludes with four repeated statements linking this state of affairs to a lack of central political leadership: “in those days there was no king in Israel, every man did what was right in his own eyes.” Although the book of Ruth is set in this historical moment, the lack of centralized political authority does not prevent its characters from displaying responsibility toward one another and fulfilling lofty ethical imperatives. In the end, the book also invokes kingship – due to Ruth and Boaz’s virtue they merit to be the progenitors of the Davidic dynasty. The book of Ruth thus represents a counter-narrative to the book of Judges – it presents kingship as a consequence of a chain of goodness, not as a Hobbesian solution to the people’s moral depravity.

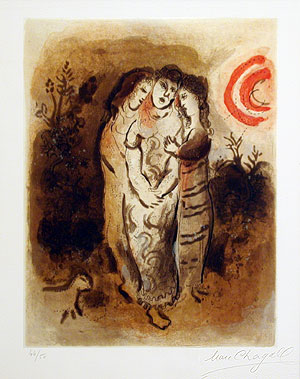

As a story about a Moabite princess who converts to Judaism, the book of Ruth also alludes to the original birth of the Moabite nation, which results from Abraham and Lot’s separation from each other in the book of Genesis. After the destruction of Sodom, Lot’s daughters sleep with him in the mistaken belief they are the last people on Earth. This unnatural and forbidden union gives birth to the nation of Moab. This is the classic stuff of tragedy, à la Oedipus Rex, and the nation Moab is rooted by the Bible in familial and moral dysfunction. Set against the backdrop of Genesis, Ruth’s clandestine nighttime encounter with Boaz carries added significance. It is a rectification or undoing of past mistakes and even a kind of homecoming to Abraham’s descendants for the wayward relative Lot.

Similarly, the book of Ruth also invokes the near-tragic episode of Judah and Tamar (Genesis 38). Boaz is a descendant of that union, and there are many parallels in the development of Boaz and Ruth’s relationship that echo the young widow Tamar’s demand that Judah also assume his responsibility as a “redeemer” for their family. Yet there are nightmarish qualities to the story of Judah and Tamar that are absent from the book of Ruth. Tamar needs to hide her identity and pretend to be a harlot in order to attract the attention of Judah. Boaz accepts Ruth as she is. Both Tamar and Ruth approach their respective redeemers in stealth and darkness, but only Ruth and Boaz end up ultimately publicizing their union with the blessings and imprimatur of their community. In extreme contrast, when Judah finds out that Tamar is pregnant, unaware that he is the father, Judah attempts to have her burned to death. That outcome is thankfully averted by Tamar’s ingenuity, but the comparison only highlights the extent to which kindness and generosity could preclude all of this potential suffering. These parallels to Genesis remind us that it would not have taken much for the story of Ruth to devolve into something much darker and more complicated, but key acts of chesed prevent a tragic outcome.

Ruth and Shavuot

The connection between the book of Ruth and the holiday of Shavuot is not obvious. Shavuot itself is a holiday with agricultural, ritual and historical dimensions. It marked the end of the wheat harvest and the start of the time when bikkurim, “first fruits,” could be offered in the Temple. According to the oral tradition, Shavuot also celebrates the giving of Torah at Mount Sinai. Some commentators point to the agricultural connection between the setting of Ruth and the holiday of Shavuot. Others point to thematic parallels such as Ruth’s acceptance of Judaism and the Jews’ acceptance of the Torah at Sinai. Yet the distinct sweetness of the book of Ruth may also be a relevant factor in considering its connection to a holiday that celebrates the acceptance of the Torah.

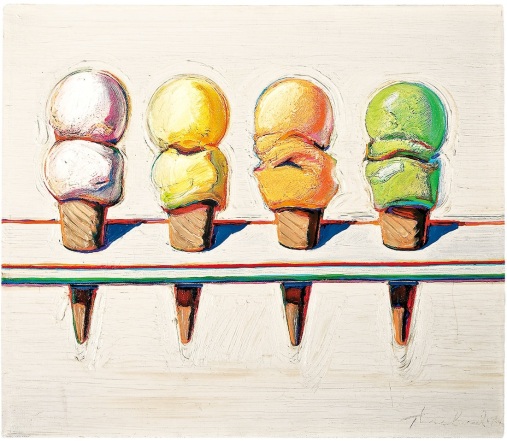

Recently, my five-year-old son asked me why we eat dairy food on Shavuot. His grandmother had intimated that he would get to eat lots of ice-cream on the holiday this year, and he was intrigued. I presented him with the traditional answer, that of the Mishnah Berurah: since the Jews did not know the laws of ritual slaughter before the giving of the Torah, they had to eat dairy until they were able to kasher their vessels and learn to prepare meat according to the strictures of Jewish law. This answer didn’t thrill him, too legalistic and convoluted perhaps. Also, it had nothing to do with ice-cream.

There is actually a range of traditional explanations for the custom of eating dairy on Shavuot, which is believed to have developed in the Middle Ages. One such explanation links dairy foods to the verse that appears in the Song of Songs (4:11),” דבש וחלב תחת לשונך,” “Honey and milk are under your tongue.” Here, the speaker imagines the lips of his beloved to be figuratively dripping with milk and honey. The midrash views the Song of Songs in allegorical terms as a poem about the relationship between Israel and God, and this particular verse is connected to Torah study. Thus, the custom may have arisen to eat dairy on Shavuot because it reflects the sweetness of the Torah itself. Perhaps it is not too far off then for a five-year old to imagine ice-cream as a crucial part of the Shavuot holiday.

The book of Ruth is not reflective of the full sweep of the Jewish Bible. To paraphrase the midrash in Ruth Rabbah, the Torah is filled with the laws of purity and impurity, it contains plenty of transgressions and plenty of mitzvot. Yet Ruth presents a particular and perhaps essential Biblical vision, one in which both sin and tragedy are only present in the distant margins, while kindness and chesed occupy the foreground. Shavuot, among its other associations, also represents a kind of coda to the yearly holiday cycle, one that begins with the fear and trembling of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. At the end of this cycle of major holidays we are left with a distinctly sweet taste in our mouth.

I like the bit about sefer Rut choosing to focus on the positive, especially in how it leaves Elimelech and his sons’ premature deaths ambiguous. Also, how Sefer Rut acts as a foil for Shoftim’s outlook on the path to kingship. Subtle but profound.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Nadav!

LikeLike

Pingback: Love and Kingship: The Book of Ruth and Jerusalem Day – The Book of Books