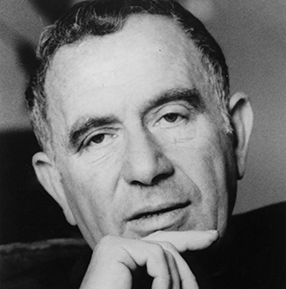

The connection between contemporary “Jewish” art and our religious tradition may feel tenuous at times. While there is something to be said regarding Jewish cultural output in all of its eclectic manifestations, many modern Jewish authors in particular seem to draw on Jewish motifs or symbols without engaging in the internal discourse of Judaism itself. That is, most of their work can ultimately best be understood within the context of broader secular Western culture. However, the poetry of the modern Israeli writer Yehuda Amichai (1924-2000) maintains a more delicate relationship with traditional Judaism, one which has always intrigued me as a religious reader. The following poem, translated by Chana Bloch, speaks to the complex interaction between Judaism, art and the associations and attachments we bring to religious life in the modern world:

Poem without an End (“שיר אינסופי”)

Inside the brand-new museum

there’s an old synagogue.

Inside the synagogue

is me.

Inside me

my heart.

Inside my heart

a museum.

Inside the museum

a synagogue,

inside it

me,

inside me

my heart,

inside my heart

a museum

The poem begins by referencing a sight familiar to many of us: the odd juxtaposition of an old restored synagogue inside a modern Jewish museum. (This image reminds me in particular of the four reconstructed synagogues in the Israel Museum, my favorite of which is the one from Suriname with its sandy floor.) For Amichai, the synagogue is not merely a relic from an outdated past, rather it lives and he lives inside it. Moreover, the synagogue lives within him and so-on, creating the never-ending cycle of the poem’s title.

Amichai, famously, identified as secular but grew up in an Orthodox Jewish home and tirelessly engaged with Jewish history, rituals and texts throughout his career. It is easy, then, to understand his connection with the world of the synagogue, but the significance of the “museum” that dwells within his heart is less clear. How does the museum function as an intermediary between the poet and his place of his worship? A museum is not a place of intimate private memories – it is a cold, impersonal meeting place of cultural artifacts dismembered from their original context. One can imagine a poet describing his bleeding heart cut out of his body and cruelly displayed for all in a museum, but the notion of a museum within that poet’s heart is more difficult to grasp.

Perhaps the museum is meant to conjure a hall of memories, neatly framed and categorized, with his childhood recollections of synagogue attendance occupying a position of importance. Alternatively, perhaps the museum is intended to introduce a note of alienation into the poem – the only way the poet can access his tradition, or even his own self, is through the austere and detached medium of the museum. Or perhaps Amichai is invoking the museum as a representation of “high” culture, a place in which religious belief and practice are concretized and turned into art. I am inclined toward this last interpretation – it is not just the Jewish faith that is embedded in the poet’s heart, but that faith is also somehow itself linked to artistic or literary expression. The way in which Judaism might manifest itself in a museum gallery, perhaps through Judaica or visual art, has a bearing on Amichai’s experience of religion. This engagement with Judaism via art becomes inextricable from Amichai’s own self as a Jew and a poet, and is then folded back into the substance of the religion itself, as represented by the synagogue in the poem’s next layer.

For Amichai, then, the fluid relationship between all of these forces also defines what a “poem” is – an unfolding song that harmonizes the disparate elements of life in a way that may not make logical sense but coheres within the context of the poem. Robert Frost memorably describes the role of the poem in this light, as “a momentary stay against confusion.” Amichai likens his relationship with Judaism to a poem in this sense.

Judaism as a Never-Ending Poem

The central texts of the Jewish religion contain large amounts of poetry or poetic language. Moreover, there is a way in which the Torah itself may be understood as one large poem. Toward the end of the book of Deuteronomy (31:19), when Moshe wraps up his departing speech to the people of Israel, God says to him, “Write down this poem [or song] and teach it to the people of Israel; put it in their mouths, that this poem may be a witness for Me against the children of Israel” וְעַתָּה, כִּתְבוּ לָכֶם אֶת-הַשִּׁירָה הַזֹּאת, וְלַמְּדָהּ אֶת-בְּנֵי-יִשְׂרָאֵל, שִׂימָהּ בְּפִיהֶם: לְמַעַן תִּהְיֶה-לִּי הַשִּׁירָה הַזֹּאת, לְעֵד–בִּבְנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל The precise content of the poem being referred to here is unclear – it may be the content of Deuteronomy as a whole or the more contained poem of “Shirat Ha’azinu” in Chapter 32. (See Rabbi Alex Israel’s excellent summary of the debate on this point here.) There is a distinct strand of Jewish thought, however, that sees the “poem” described in Chapter 31 of Deuteronomy as referring to the Torah as a whole. That is to say, the Torah itself, both the five books of Moses and the living transmitted experience of it, may be understood as a kind of poem as well. Our constantly unfolding, constantly evolving encounter with the Torah, which builds upon centuries of interpretation and experience, is also “a poem without an end.”

Robert Alter’s The Poetry of Yehuda Amichai

Many of Amichai’s poems explore the complex layers of the sacred and mundane, ancient/traditional and modern, that characterize the land of Israel, his beloved city Jerusalem, and even his own self. Robert Alter’s terrific new edition of Amichai’s poetry in translation, The Poetry of Yehuda Amichai, highlights these motifs and those discussed above from “Poem Without an End.” The speaker of “Jerusalem, 1967” describes his condition of longing for Jerusalem from abroad:

…I played the hopscotch

of the four strict squares of Yehuda Ha-Levi:

My heart. Myself. East. West.

(trans. Stephen Mitchell)

Throughout the anthology we get the sense that Amichai, even when he is writing within Israel, is acutely attuned to these various layers and tensions: “my heart,” “myself,” “East” and “West.” Many of his poems represents attempts to harmonize these tensions and present a continuum of past and present, Eastern and Western values, that coheres at least throughout the span of the poem. These attempts are not always easy, as he says in “I Am Tired”:

I am tired like a very ancient language

invaded by foreign words.

I cannot defend.

(trans. Robert Alter)

Amichai’s attempts to negotiate between ancient and modern tensions exhaust him, at times it seems like one force or another is going to prevail. In the famous poem “Mayor” for example, despite the fact that the contemporary mayor of Jerusalem tries to develop and modernize the city, his efforts are perpetually mocked by the ancient anarchy that threatens to descend. As Amichai writes:

It’s sad

To be Mayor of Jerusalem.

It is terrible.

How can any man be the mayor of a city like that?

What can he do with her?

He will build, and build, and build.

And at night

The stones of the hills round about will crawl down Towards the stone houses,

Like wolves coming

To howl at the dogs

Who have become men’s slaves.

(trans. Assia Guttman)

In the “Love of the Land” a poem that Alter newly translated for this anthology, Amichai describes the complicated and contradictory emotional geography of Israel, and the impossibility of truly reconciling all of the disparate entities contained within. Nevertheless, he attempts to bind all of these competing elements together, at least for a “momentary stay against confusion”:

…Thus I can feel the whole land

when I close my eyes: sea-valley-mountain.

Thus I can remember what happened there

all at once, as a man remembers his whole life

at the moment of his death.

Here, as in “Poem without an End,” Amichai constructs a framework in which the various threads of his identity and that of Israel can cohere in a meaningful way. Yet the fact that he perpetually constructs these frameworks, and also reveals their limitations, indicates a never-ending quality to the pursuit.

Shir Ein-Sofi

It is difficult to entirely appreciate Amichai’s rich engagement with the Jewish tradition when reading him in translation. Alter’s new anthology is in part an attempt to restore at least some of the classical Jewish allusions that are missing from other English translations. Yet in the interest of maintaining the flow of the individual poems, and not burdening the reader with excessive footnotes and commentary, there is only so much Alter can do to convey the full picture of Amichai’s engagement with Jewish sources. In the new anthology, Alter re-translates “Poem without an End” into a slightly more staccato version that better reflects the cadences of Hebrew itself, and gives it a new title: “Infinite Poem.” Personally, I prefer the sound of Chana Bloch’s translation above, and I like that she omits the final punctuation mark at the end of the poem, a nice choice for a poem that is never meant to be completed. However, Alter’s revision of the poem’s title from “Poem without an End” to “Infinite Poem” may perhaps be an attempt to more faithfully render the original Hebrew title of the poem: שיר אינסופי (“Shir Ein-Sofi”). “Ein-Sof,” which means “endless,” is also one of the Kabbalistic names for God. Amichai uses this term for dramatic effect at the end of “The Diameter of the Bomb,” (“קוטר הפצצה“) “making a circle with no end and no God,” “את המעגל לאין סוף ואין אלוהים.”

In the case of “Shir Ein-Sofi,” it is possible that the introduction of the term “Ein Sof” in the title lends a theological quality to the poem, which suggests meanings that transcend the poet’s own internal makeup. God too is present in the never-ending poem that defines Amichai’s relationship with Judaism and art. With the phrase“ein sofi,” we are introduced to the idea that “never-ending” need not indicate futility, but may also point to a kind of transcendent holiness. There is more to be said about the many ways in which Judaism or the Torah may be likened to a “poem without an end,” but I appreciate the subtle way in which Amichai opens up this potential line of thought.

Beautiful post!! Well articulated and as poetic as the poems you write about!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I do not think of museums as “cold, impersonal meeting place ” but as a great treasury of our culture. A museum in my heart means l/ he holds the whole life of the Jews in his heart. Thank you for your piece, Sarah.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Beautiful! I had considered, and perhaps should have mentioned in this post, how the museum vs. the synagogue may also refer to the experience of the Jewish ppl in history/time vs. the Jewish religion itself. Thank you for this insight.

LikeLike

Just happened to find this blog and very happy I did. I really hope you will continue to write. This was a very beautiful essay and gave me a lot to think about. I hope you will analyse more poems as for those of us who are not literature students etc, it is really eye opening.

LikeLike

Thanks so much Avi! It’s been a busy month for me but some new posts are in the works, in the meantime feel free to subscribe for regular updates.

LikeLike

Exodus

in memory of Jehuda Amichai

You are the Shepherd

leading out the words from the desert

I come to the Faithful City

repeat the Midrash Genesis Rabba

after the destruction of the Temple

I find the promise of eternity

I see you under the cedarwood

reading the Mishna and the Gemara

the last Hebrew poet

and I can’t pronounce your name

LikeLiked by 1 person

Beautiful, thank you for sharing this

LikeLike

Alter’s translation curiously omits the second reference to a synagogue within the museum (it consists of just 14 lines, rather than 16). I can’t help but wonder whether this is:

1) a typo

2) a deliberate edit on the part of Alter, or

3) an edit by Amichai himself (perhaps in a later edition of the poem).

Could you (or anyone) please address this question?

Here is Alter’s translation:

Within the brand-new museum

an old synagogue.

Within the old synagogue

me.

Within me

my heart.

Within my heart

a museum,

within it

me,

within me

my heart,

within my heart

a museum.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great observation. Losing that second reference to a synagogue does change the valence of the poem, though it also turns it into a proper sonnet! I am going to look into it and try to get back to you.

LikeLike

Actually, after leaving my earlier comment, I realized I could perhaps inquire with Professor Alter directly. He very graciously (and promptly) responded that it is in fact a typo, which he spotted afterward, and it will be corrected in future printings.

LikeLike

Thank you for the follow-up! Glad I went with the Chana Bloch translation for this post 🙂

LikeLike

“A museum is not a place of intimate private memories – it is a cold, impersonal meeting place of cultural artifacts dismembered from their original context. “ I agree with where Am started. The museum is warm and its art is the beautiful crafting of thoughtful, sensitive souls reaching out to the hearts and minds of unknown peers. It inspires the spirit, maybe toward a holy spirit in a synagogue. The heart, the museum, the synagogue, are all related, sometimes joyous, other times sad, but soulful.

LikeLike